Schema theory, developed by Jeffrey Young, proposes that early experiences can lead to the development of deeply held beliefs and feelings about oneself and the world, called “schemas.” These schemas shape our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors throughout life. Understanding how your experiences have shaped your responses to the world can be helpful. In many ways, these familiar ‘adaptations’ form our repetitive responses and habits to managing the world and relationships. This post explores the various schemas and how they appear in parts-work.

The schemas are organised into five categories: disconnection and rejection, autonomy and performance, lack of limits, other-directed, and self-hatred and self-control.

Here is a summary of the five categories of schemas.

Disconnection and Rejection.

This group of schemas in general relate to early attachment trauma, where safety and trust have been consistently missing, where our natural authenticity has been rejected. Where we learn that our needs are not important by neglect or punishment. The main messages are that you or something about you is shameful, unwanted or different. We can develop strategies based on protection from others or directed at ourselves as unworthy of attention, and that we don’t belong. Experiences and feelings of not being heard or understood often connect to these schemas.

Autonomy and Performance.

This group of schemas relate to our sense of competence and independence. Belief that you need to be cared for and can’t exist independently. There are beliefs that you can’t make decisions, and others know better than you—beliefs around not being able to survive or deal with life on your own. There is a heightened sense of vulnerability and lack of agency. These schemas will include feelings of failure, impostor syndrome, and inability to succeed. Growing up with experiences where your achievements were never good enough, you were compared to others, or you were overprotected so you didn’t develop your sense of agency.

Lack of Limits

Folks who grew up without boundaries can be adversely affected by an unrealistic sense of self or privilege. As children, we need to learn our limits and self-control. When these are missing, we have schemas that lead to a sense of superiority and difficulty controlling impulses to follow through on agreements and goals.

Other-directed.

In this set of schemas, people have had to put themselves aside to maintain early relationships with caregivers, often moulding themselves to what others wanted or denying their experience to gain approval. In most early relational betrayals, neglect, and abuse, there is a degree of other-focused behaviour for survival. Specifically, it can look like people-pleasing, caretaking (feeling you have to fix others’ lives), and believing you have to submit to others’ will or desires.

Negatively oriented and excessive self-control.

Tendencies towards the negative aspects of life and the negative aspects of self. Even when things are seemingly going well, there is a focus on when it will all collapse. A fear of making mistakes and trying to control them leads to perfectionism, rules-based and preoccupations with time and efficiency. Emotions and vulnerability are experienced as creating chaos and must be controlled, leading to excessive inhibition of spontaneous action and desires. A focus on intellect versus emotion.

How might we work with these schemas experientially and holistically?

Traditionally, schemas have been associated with a cognitive behavioural way of working, but we see these schemas in our work all the time. At Turning Point Therapy, we work from a somatic and relational perspective, focusing on how our clients experience their triggers (reactions) somatically, emotionally, and cognitively. So we work with schemas as they come up in association with memory, our nervous system (fight/flight), trauma response, emotion and feelings. We bring awareness to these associations that lead to the protective parts.

Exploring an example.

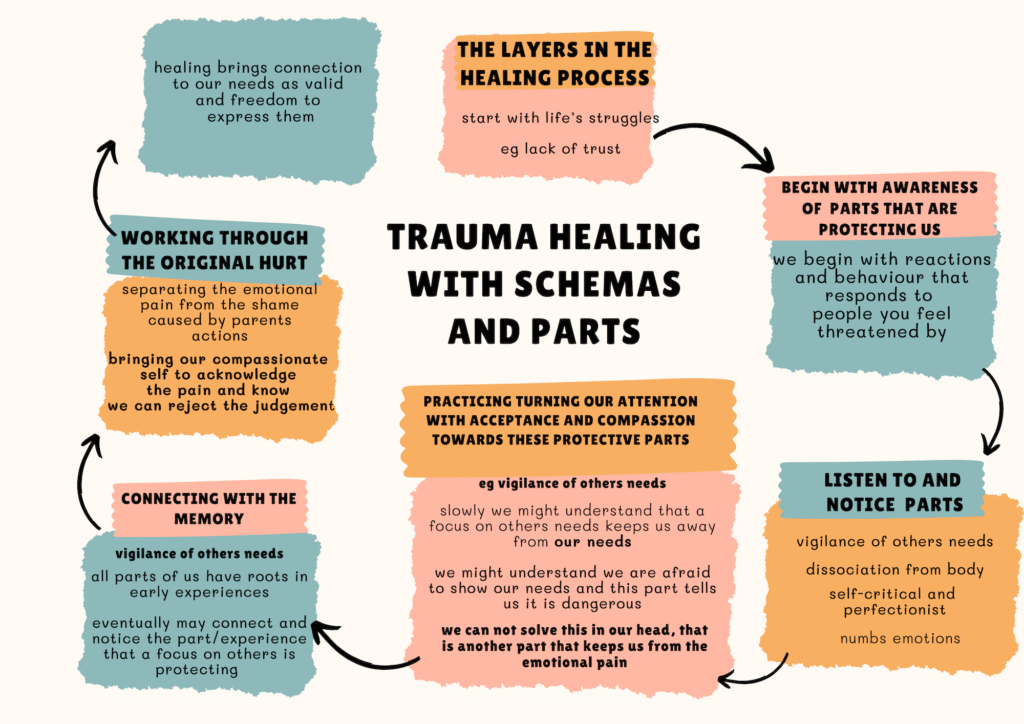

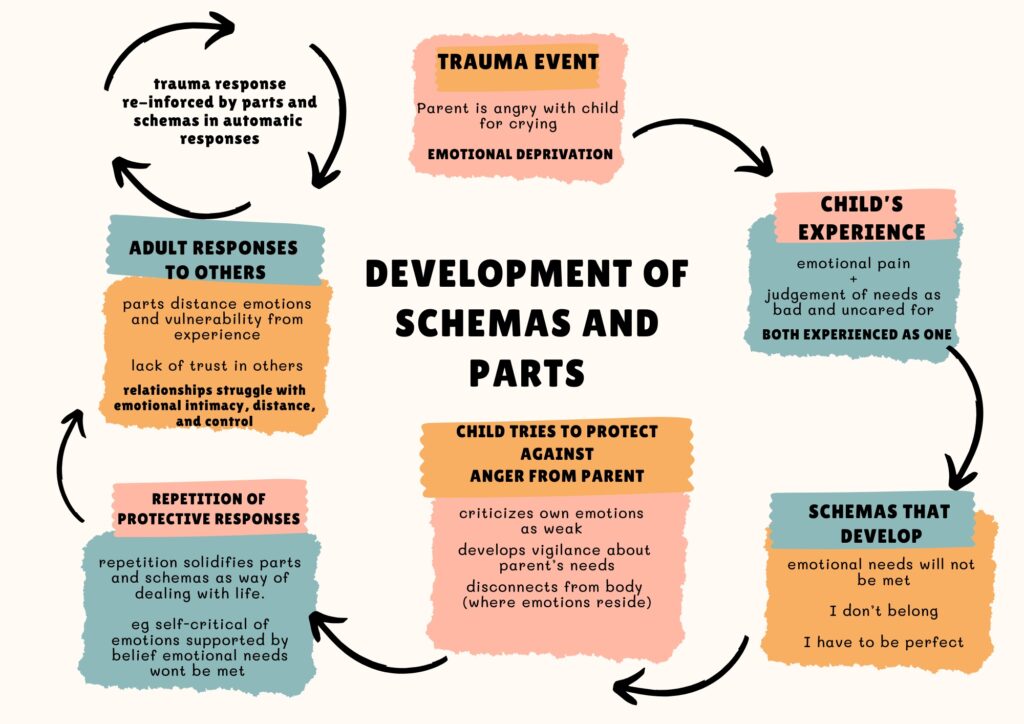

The diagrams below show the development of schemas and parts and the healing process, which involves the reverse of the development.

A few highlights in the development process.

The child’s experience is important to note how the pain and the judgement become one experience. The judgment that your emotions are shameful is simultaneously accepted, along with the pain of the parent’s anger. They become one experience as the child cannot reject the judgment expressed with the adult’s hurtful behaviour. A child is unable to say to the adult you’re hurting me, and that is wrong. Instead, the only conclusion is (in this case) my emotional need is wrong because they take on the judgment. This is how shame is inevitable when the pain is unacknowledged and unprocessed. Schemas develop as ways of understanding ourselves and the world based on this experience.

Parts are how we try to deal with the world based on this experience, and schemas continue to inform these protective parts of us.

What we understand as a trauma response are these repetitive parts, in this example, trying not to make others angry, disconnecting from their pain, and blaming themselves for others’ bad behaviour.

In the healing process, we can see how we start with what is coming up and work through the protective parts to eventually experience the emotional pain that our adult brain can help separate from the judgment. We heal when we can acknowledge the pain and reject the judgment. We can’t just intellectually tell ourselves this, as the protective layers carry the schemas that reinforce the protective parts, and we have to work through them to develop self-compassion on the route back to sit beside the child part with compassion and acceptance.